2024 election

Firsthand Insights: The Unique Voting Challenges Confronting Indigenous Arizonans

Covering the Arizona primary election on Tuesday shed light on the significant challenges faced by Indigenous voters in the Navajo Nation. My day involved visiting various polling locations, but what struck me most was the sheer distance and time it took—a stark contrast to experiences in Maricopa County.

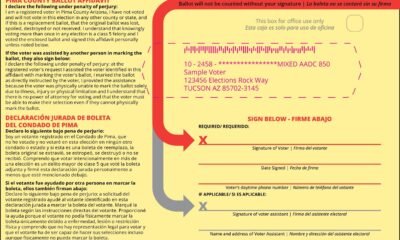

Driving around the Navajo and Hopi Nations, I covered over 250 miles and visited 10 polling stations in nearly 10 hours. In comparison, Maricopa County offers over 230 polling stations, whereas Apache County has only 44, and Navajo County just 39. The vast distances between polling locations make it considerably more difficult for Indigenous voters to participate in elections.

The Navajo Nation spans parts of Apache, Navajo, and Coconino counties, while the Hopi Nation is spread within Coconino and Navajo counties. Voting often involves crossing these expansive lands, making the journey to the polls a day-long event for many. For example, my family needs about an hour to complete the round trip to our local polling station.

Throughout the day, I observed consistently low voter turnout, with no long lines and only a handful of people at each site. An election official at the Kin Dah Lichii Chapter House explained that many tribal employees vote after work, around 3 p.m., which could explain the sparse turnout earlier in the day.

While some voting locations displayed an energetic atmosphere with local advocates distributing refreshments, others simply served as quiet spaces for voters to cast their ballots. My father often reminisces about voting near closing time to socialize, a tradition that remains in some areas of the Navajo Nation.

Despite this, the majority of campaign signs were for tribal, rather than state or federal, candidates. This highlights a gap in electoral engagement from higher-level political campaigns toward these communities.

Encouraging voter participation in these remote areas is vital. Many residents, like those in Keams Canyon, are not even aware of Election Day or where to vote. This disconnect emphasizes the need for enhanced voter education and outreach.

Indigenous people in Arizona face a unique historical context; they were denied citizenship and the right to vote until 1924 and 1948, respectively. However, their voting bloc is substantial, representing over 305,000 potential voters, which could significantly influence election outcomes.

In the 2020 general election, Indigenous voters played a critical role, with a substantial majority casting ballots for Joe Biden, contributing to Arizona’s shift from a traditionally red to a blue state. Yet, efforts by state and federal campaigns to engage these voters remain limited.

This election cycle, with the presidential election approaching, it’s imperative for candidates to recognize the importance of Indigenous voters in battleground states like Arizona. Without comprehensive voter education and engagement, these communities may continue to face barriers in exercising their electoral rights.

Indigenous voter advocates are working tirelessly at the grassroots level to bridge this gap. However, broader efforts are needed from political campaigns and organizations to ensure these voters are not overlooked in the democratic process.