2024 Election News

Arizona Bridges Language Divide to Offer Navajo Voters Audio Ballots

This story was originally published by Votebeat in partnership with ICT. Votebeat is a nonpartisan news organization covering local election administration and voting access.

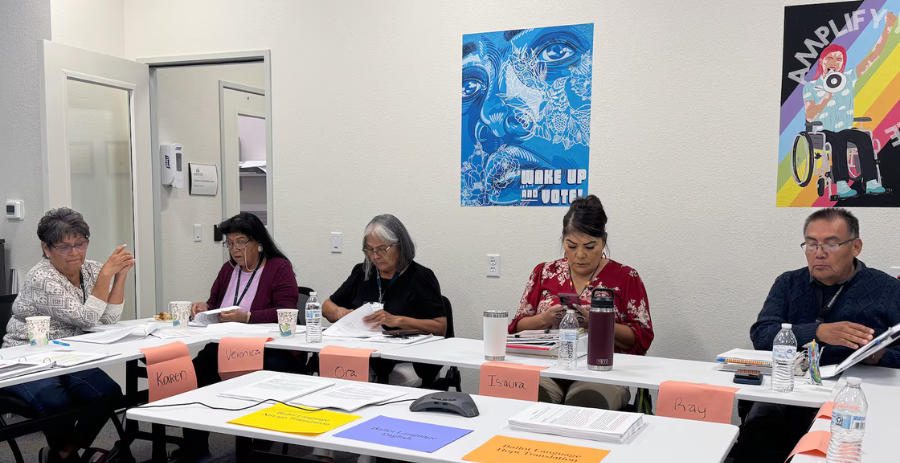

In Flagstaff, a dedicated group of Navajo speakers met to tackle the complex task of translating key ballot propositions for the upcoming Arizona elections. Their first challenge? Accurately conveying the meaning of fentanyl within their language.

Conversation turned serious as they dissected the term “azeé,” which denotes medicine but carries a healing connotation. The translation team recognized that this does not encompass the severity of the issue at hand. “Azee’ sends the wrong message,” one member remarked. The endeavor at hand was not merely translation; it was about ensuring clarity for voters within the Navajo Nation.

The team faced a tight deadline, with a total of 13 propositions to translate into Navajo in preparation for the November ballot. Voters not proficient in English must understand these propositions, especially given the historically oral nature of their language.

This election cycle presents several contentious issues, including abortion rights and open primary elections. While media coverage has scrutinized the English wording, the Navajo translations often operate under the radar, despite federal mandates ensuring language accessibility under Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act.

Over the years, Arizona courts have ruled against election officials for insufficient support to non-English-speaking voters, highlighting the critical need for more comprehensive legislative compliance. Following federal guidelines, several counties, especially those with significant Indigenous populations, are required to provide translations in multiple Native languages, including Navajo, Hopi, and Apache.

Meeting discussions spanned two days, providing insight into the translation process’s intricacies. A Votebeat reporter and videographer gained rare access to observe the final day, revealing the challenges officials face when translating ballots, especially for those languages that rely heavily on oral tradition.

The voting power of the Navajo population is substantial; approximately 71,000 Arizonans of voting age speak Navajo, with about ten percent lacking fluency in English. Missing translation resources can significantly impact this group, whose voices have historically influenced key political outcomes, including the 2020 presidential election.

According to a settlement from 2019, Arizona’s Secretary of State’s Office must provide certified Navajo translators to assist voters. However, recent discussions at the translation meeting only addressed the propositions themselves, overlooking the accompanying yes/no descriptions crucial for understanding. Whether a comprehensive audio translation will be available to voters remains uncertain.

The selection of language in translations can evoke cultural sensitivities. For instance, Proposition 139, concerning abortion rights, posed unique challenges. Traditional Navajo beliefs largely disapprove of abortion, complicating how its terminology is approached in translation. Linguists like Melvatha Chee caution that softened translations risk misinforming voters regarding the actual changes proposed in the law.

Similar debates arose around Proposition 313, concerning penalties for child sex trafficking. Participants highlighted the potential misunderstandings arising from inappropriate language choices, illustrating the delicate balance between cultural respect and accurate communication.

Despite efforts to enhance translation services, critics argue that significant gaps remain. Leonard Gorman, executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, has consistently found the translations lacking. He stresses that voters must fully grasp the propositions to exercise their rights effectively.

Arizona’s Secretary of State’s Office maintains that improvements have been made since previous lawsuits, yet the effectiveness of these changes is under scrutiny. Both local advocates and legal experts argue that the translations should cover all election material, not merely the ballots, to ensure meaningful participation in democracy.

The last-minute nature of the election translations illustrates the broader issue of language accessibility for Native voters in Arizona. As some officials have noted, robust action is overdue to align practice with legal expectations. The ultimate success of the Navajo voters will hinge on how well these translation challenges are navigated in the weeks leading to the election.