Arizona Department of Environmental Quality

Tribe Fights Uranium Transport Threatening Ancestral Lands: A Fight for Heritage

Orange roadside markers are staked along the six-mile gravel road leading from the Pinyon Plain uranium mine, indicating the road is a uranium haul route. The small markers are the only signage along the road showing it is a uranium haul route. Photo by Shondiin Silversmith | Arizona Mirror

Dianna Sue Uqualla, a member of the Havasupai Tribe, honors her heritage by wearing traditional moccasins and regalia during visits to Red Butte Mountain, a site of deep cultural significance. This mountain is not merely an outdoor landmark to the Havasupai people; it represents their ancestral homeland and a source of medicinal plants, wildlife, and materials essential for survival.

“You can still see the fire pits along the tree lines,” Uqualla stated, referencing the physical marks left by her ancestors. She views the mountain as a living source of the medicinal resources that have sustained her people throughout history.

In contrast to typical perceptions of nature, Uqualla emphasizes that many Native Americans see these places as sacred. For them, Red Butte Mountain is imbued with spiritual significance, serving as a venue where medicine people once gathered.

Regrettably, the ongoing operations at the Pinyon Plain Mine, located just three miles north of Red Butte Mountain, pose a grave threat. Since early 2024, uranium ore has been extracted and transported along designated routes that directly pass by the sacred site.

Owned by Energy Fuels, Inc., the Pinyon Plain uranium mine occupies U.S. Forest Service land within the Kaibab National Forest. This area is integral to multiple tribes, including the Havasupai Tribe, who argue that the mine jeopardizes drinking water, sacred sites, and the surrounding natural environment.

Uqualla lamented the decline of traditional practices; fewer community members feel safe praying at Red Butte Mountain due to contamination fears from the mining operations. “It’s a blessing for the land,” Uqualla expressed, noting that community gatherings for healing and prayer have become rare since the mine began operations. Despite these changes, she still makes her visits to connect with her heritage.

The start of uranium transport in July was deeply unsettling for the Havasupai. Uqualla shared her disappointment, citing the mining company’s failure to provide the promised notice to the tribes. “That was not right,” she emphasized, critiquing the decision to commence transport early in the morning when many would fail to notice.

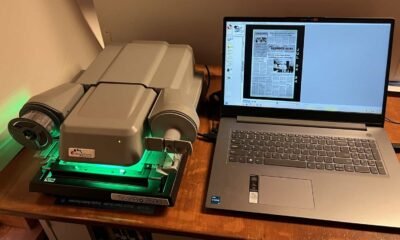

Energy Fuels plans to transport uranium using 24-ton haul trucks, with up to ten trips occurring daily. The trucks will navigate a network of gravel roads through the dense Kaibab Forest, eventually reaching State Route 64. Uqualla pointed out the inadequacies of the route’s only indicators—simple orange roadside markers—questioning their visibility and effectiveness.

As the trucks near Red Butte Mountain, Uqualla expressed that the dangers of contamination extend significantly beyond the mine’s immediate vicinity. She fears a catastrophic accident on the highway could unleash uranium ore into the environment, saying, “Even with emergency plans in place, the contamination would already have occurred.”

All shipments of uranium ore from the mine are marked with a yellow placard reading “RADIOACTIVE,” but Uqualla and other tribe members believe that insufficient labeling keeps the public uninformed. Caska, another tribe member, called for transparency, asking why the mining company would not make their cargo easily identifiable if they were not trying to hide something.

Decades of opposition to uranium mining by the Havasupai have generated a strong sense of resistance among tribal leaders. Uqualla noted the cumulative efforts of her community against mining since her childhood. “Now, I have become the elder that is fighting for this,” she said, signaling a continuing commitment to advocate for protecting their land and culture.

Historically, the Pinyon Plain Mine poses risks of flooding, threatening groundwater resources that serve as vital springs for the Havasupai and other communities. In 2020, a federal judge ruled in favor of the mine amidst ongoing opposition from the Havasupai Tribe and environmental groups. However, efforts continue, including requests for a new environmental impact statement to scrutinize the mine’s implications.

The tribe recently celebrated a temporary halt in uranium transport after advocating with the Arizona Attorney General and Governor. Caska expressed cautious hope, believing that their voices are being heard in this contentious battle. “It’s going to be a hard fight,” she said, underscoring the challenges that lie ahead.

Concerns remain high, especially as negotiations evolve between Energy Fuels and the Navajo Nation. Caska pointed out the oversight of including the Havasupai Tribe in discussions about the mine’s operations, stressing, “They’re coming out of our territory, so we should have the same say.”

Both Uqualla and Caska are determined to ensure that future generations can inherit a healthy and vibrant ancestral homeland. “This is where we came from,” Caska reiterated, emphasizing the importance of maintaining cultural practices and traditional ways of life in the face of formidable challenges.