Business

Native American Patients Face Debt Collections Over Unpaid Government Bills

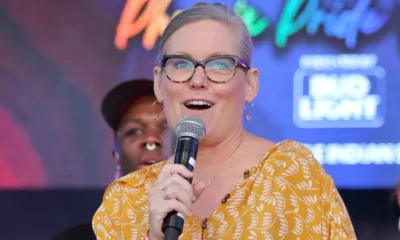

Tescha Hawley discovered that hospital bills for her son’s birth had been sent to debt collectors only while checking her credit score, a process that thwarted her home-buying plans. The hefty debts, amounting to several thousands of dollars, were erroneous claims against her, as the federal government was responsible for covering them. A citizen of the Gros Ventre Tribe, Hawley resides on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, where the Indian Health Service (IHS) struggles with chronic funding and staffing shortages.

Hawley’s local IHS hospital lacked the facilities to handle deliveries. Accordingly, staff assured her that her care at a privately owned hospital over an hour away would be covered by the Purchased/Referred Care program, which is intended for Native Americans needing services beyond what agency-funded clinics or hospitals can offer. Federal regulations explicitly state that patients approved under this program shouldn’t bear any costs.

However, tribal leaders and health officials highlight that patients frequently receive bills due to systemic delays or errors within the IHS, financial intermediaries, hospitals, and clinics. The ramifications of wrongful billing can linger for years, damaging credit scores and eventually hindering access to loans or forcing individuals into higher interest rates.

A federal report released in December by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau revealed that these long-standing issues contribute to a significantly higher prevalence of medical debt collection in Native American communities, nearly double the national average. The report specifically noted that delays in payment from the program exacerbate the problem and that hospitals often demand more money even after bills have been settled.

Hawley’s struggle began when her son was born in 2003. It took her an additional year to secure a home purchase, and the debt did not vanish from her credit report for seven years. As a cancer survivor, she continues dealing with the referral program, recently receiving multiple overdue bill notices.

During a U.S. House committee hearing in April, Frank White Clay, chairman of the Crow Tribe, detailed the negative consequences of wrongful billing. He recounted stories of veterans being denied home loans, elders facing reductions in their Social Security benefits, and students unable to access federal aid. “Some of the most vulnerable people are being harassed daily by debt collectors,” he stated.

The issue is pervasive. A high-ranking IHS official even found referral-care debt on her credit report during a background check. Native Americans wrestle with disproportionately high rates of poverty and health issues, trends linked to limited healthcare access and the lingering effects of federal policies steeped in racism.

White Clay characterized the problems with the referral program as a breach of the U.S. government’s treaty obligations to provide health and welfare support in exchange for tribal lands. His testimony surfaced during discussions on the Purchased and Referred Care Improvement Act, which aims to mandate the IHS create a reimbursement mechanism for patients wrongfully billed. This bill was approved by committee in November and has been forwarded to the full House for consideration.

Another legislative proposal, the Protecting Native Americans’ Credit Act, seeks to shield patients’ credit scores from repercussions arising from such wrongful debt; however, by mid-December, it had yet to undergo any hearings.

Although the precise number of wrongfully billed individuals remains uncertain, the IHS admits that significant improvements are needed. The agency is actively developing a dashboard to enhance tracking and accelerate bill processing. Furthermore, efforts to fill a vacancy rate exceeding 30% in referred-care staff are underway.

Melanie Egorin, an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, noted that the proposed legislation lacks provisions for punishing healthcare providers that consistently bill patients incorrectly. She acknowledged that the absence of enforcement represents a significant issue.

Tribal leaders, however, expressed concerns that introducing penalties could backfire. White Clay cautioned that some clinics already refuse to treat patients if IHS hasn’t cleared payment for previous services, warning that penalties could exacerbate this issue. Such an outcome would force tribal members, often traveling long distances for specialty treatments, to travel even farther.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau report corroborates that clinics are increasingly turning away referred-care patients due to persistent payment issues. To combat this, the bureau and IHS recently communicated with healthcare providers and debt collectors, stressing that patients should not be held accountable for costs related to program-approved care.

Joe Bryant, a key figure in the IHS overseeing referral program enhancements, indicated that patients may appeal to credit bureaus for the removal of debts due to inappropriate billing. Discussions of legislative solutions have also been influenced by tribal leaders from the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, where wrongful billing issues emerged in 2017 after a regional IHS office assumed control of their referral-care program.

In 2022, management of that program shifted back to local staff, revealing significant billing discrepancies amounting to approximately $24 million. While progress is being made to address this backlog, cases of wrongful billing persist, demonstrating the continuing challenges within the system.

As some tribes strive for greater autonomy in managing their healthcare facilities, concerns linger about whether this approach releases the federal government from its responsibilities. Beyond billing issues, underfunding remains a pressing concern; the current year’s $1 billion budget falls $9 billion short of the necessary funding according to tribal health and government leaders.

Dr. Donald Warne, an Oglala Sioux Tribe member, criticized the proposed legislation as inadequate, emphasizing that only fully funding the IHS can truly alleviate the burdens associated with the referral-care program. Back in Montana, Hawley stands ready to challenge every new bill falling under the referral coverage. “I’ve learned not to trust the process,” she remarked.