Business

Media Matters: Essential Guide to Understanding Libel Law

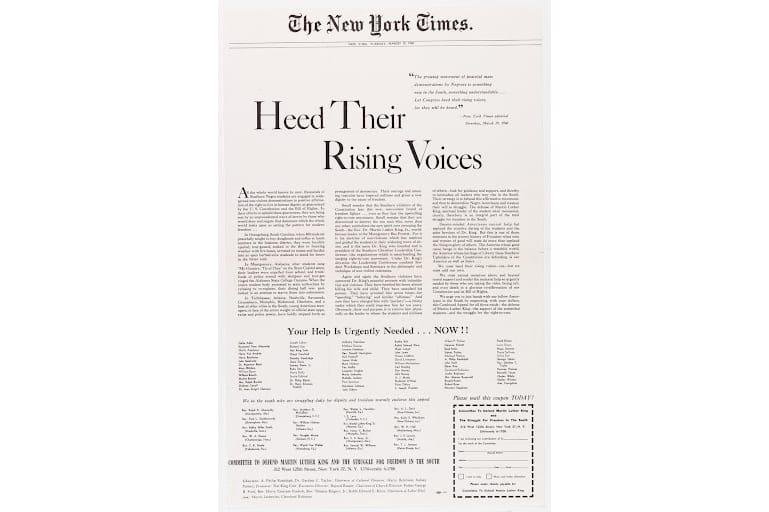

The significance of a full-page advertisement in the New York Times published on March 29, 1960, by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King cannot be understated. This influential ad condemned police tactics in southern cities, particularly Montgomery, Alabama, during Civil Rights demonstrations. It directly criticized those undermining King’s movement, labeling them as “southern violators of the Constitution.” A host of notable figures, including Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, and Eleanor Roosevelt, lent their names to this powerful petition.

L.B. Sullivan, the city commissioner of Montgomery, claimed the ad defamed him indirectly and took legal action, ultimately winning $500,000 in Alabama courts. However, the New York Times appealed, leading to a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that reversed the decision based on First Amendment protections. This ruling established New York Times v. Sullivan as a pivotal precedent, ensuring news outlets remain shielded from frivolous lawsuits aimed at stifling journalistic inquiry.

Six decades later, the case continues to serve as a protective barrier against the misuse of libel laws. Although the First Amendment prohibits Congress from limiting freedom of speech and press, it does not protect against obscenity, plagiarism, or libel — defamatory statements that can damage reputations. The legal complexities surrounding libel involve distinguishing between private citizens and public figures. Private citizens face a lower bar for proving harm, while public figures must meet the stringent “actual malice” standard.

Concerns have resurfaced about the sustainability of Sullivan’s protections. David Enrich, a business investigations editor for the New York Times, has been focusing on instances that might inspire the Supreme Court to revisit this landmark case. He cites arguments from various legal professionals who argue that the current requirement of proving actual malice is excessively burdensome for public figures.

One notable advocate of this perspective is David Logan, a former law school dean whose 2020 article called for a reassessment of Sullivan’s standards. Logan posits that with the decline of traditional reporting and oversight, the risk of untruthful reporting is heightened, suggesting the need to reevaluate the actual malice threshold. Critics, including Enrich, challenge this assertion, noting the lack of supporting examples.

Meanwhile, the influence of social media and its rapid dissemination of information complicates the libel landscape. Logan argues that the sensationalism prevalent on these platforms necessitates a weakening of Sullivan’s protections, but Enrich counters that social media companies are largely shielded from liability under existing laws.

Discussions within the Supreme Court reflect this ongoing debate. While Justice Clarence Thomas has expressed skepticism towards the national news media, he previously acknowledged the essential role of a free press in a democratic society. He has not indicated a desire to alter libel standards but has raised questions about the continuing relevance of Sullivan.

Reflecting on the historic impact of Times v. Sullivan, Enrich emphasizes that the ruling demarcates the United States from other democracies, reinforcing the importance of free expression as a check on power. This week, the Supreme Court opted not to hear an appeal from a wealthy Trump supporter seeking to overturn Sullivan, though it has been noted that Justices Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have previously called for reconsideration of the case.

As the landscape of journalism remains in flux, the future of Sullivan and its implications for free speech and accountability in reporting hangs in the balance.

Richard Campbell, a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media Journalism & Film at Miami University, serves as the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.