Business

Hanukkah and Christmas: Transformative Celebrations Through the Ages

Hanukkah, often mistakenly conflated with Christmas, stands on its own as a significant Jewish festival. Every year, various articles remind the public of this distinction, as the Festival of Lights seems to be increasingly overshadowed by its Christian counterpart. Though Hanukkah is considered a minor Jewish holiday, characterized by its timing in the liturgical year, it has grown in cultural importance, particularly in the United States.

Retailers and educational institutions now recognize the festival by prominently displaying menorahs and incorporating Hanukkah-themed songs in seasonal events. Public menorah lightings organized by groups like Chabad often bear a resemblance to Christmas tree ceremonies, subtly blurring the lines between the two celebrations. While menorahs are religious symbols, their treatment as mere decorations in many spaces overlooks their rich cultural significance.

My research, primarily focused on interfaith families, reveals the complexities surrounding these holidays. Many Jewish Americans express concern that Hanukkah’s essence is fading amidst the vibrancy of Christmas celebrations. Yet, the history of both holidays is more nuanced than these comparisons suggest.

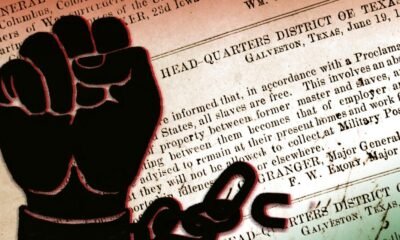

The origin of Hanukkah traces back to a historic struggle against forced assimilation. In 168 B.C.E., the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV imposed severe restrictions on Jewish practices. The Maccabees, a Jewish resistance group, fought back against both external oppression and internal cultural assimilation. This rebellion is commemorated during Hanukkah, highlighting a pivotal moment in Jewish history.

Upon reclaiming their temple, the Maccabees encountered a dwindling supply of oil, meant to sustain an eternal flame. Miraculously, this oil lasted for eight days, an event celebrated today through the tradition of lighting the menorah over eight nights and enjoying oil-based foods.

However, contemporary Hanukkah celebrations, characterized by “Hanukkah bushes” and extravagant gifts, do not reflect the festival’s authentic traditions. Such practices, while novel, are far removed from the historical practices that have endured for centuries.

American culture, predominantly shaped by its Christian roots, has undeniably influenced Hanukkah’s modern observance. The intertwining of cultural practices sheds light on how each holiday evolved following the Industrial Revolution. Before this shift, both Christmas and Hanukkah were celebrated differently, with an emphasis on community festivities rather than individual family gatherings.

The maturation of these celebrations into commercial and familial occasions stemmed from societal changes and economic demands. Early 19th-century campaigns sought to redefine Christmas as a domestic holiday, emphasizing consumption and family life.

As the market for affordable goods expanded, both Jews and Christians became recipients of the same advertisements for festive items, leading some Jewish families to adapt their celebrations accordingly. Yet, historian Dianne Ashton’s research suggests that Hanukkah’s transformation was not simply an imitation of Christmas, but a response to evolving cultural dynamics.

Hanukkah, primarily celebrated within the home, offered Jewish women a crucial role, paralleling the domesticity seen in Christmas traditions. It emphasized familial bonds, especially amid the challenges of immigration. By including children in candle lighting rituals once reserved for men, families encouraged a connection to their heritage.

In America, the freedom experienced by Jewish citizens allowed for varied levels of cultural engagement. Some chose to disengage from their Jewish identities entirely, while others found meaning in how they celebrated Hanukkah within the broader context of the holiday season. This adaptation, though it may appear as assimilation, symbolizes a survival strategy amid changing times.