faith

For Enslaved People, the Holiday Season Sparked Revelry—and Resistance

During the era of slavery in the Americas, holidays provided enslaved individuals with unique experiences. Though slave owners offered larger portions of food, alcohol, and extra days of rest, these gestures were far from generous. Frederick Douglass, the renowned abolitionist, noted that such offerings aimed to maintain control and prevent escapes or uprisings among enslaved people.

Despite these tactics, many enslaved individuals utilized the holiday breaks to plan escapes and revolts, as explored in my recent book, “Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery.” Across the Americas, enslaved populations often celebrated Christmas, deeply intertwined with the prevailing Christian traditions from regions like Alabama to Brazil.

Consider Solomon Northup, whose harrowing experiences were depicted in the film “12 Years A Slave.” Born a free man in New York, Northup was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana in 1841. He reported that during the holidays, enslaved people received between three and six days off, which he described as a “carnival season with the children of bondage.”

Northup recounted a Christmas dinner hosted by a slave owner in central Louisiana, attracting around 500 enslaved guests from neighboring plantations. For them, it was a rare chance to feast, enjoying meats, vegetables, fruits, and desserts after enduring a year of meager portions.

Holiday celebrations have roots in the earliest days of slavery. For instance, Jamaica’s Christmas masquerade, Jonkonnu, has been celebrated since the 17th century. A 19th-century artist illustrated this festivity, showcasing enslaved musicians playing instruments made from animal parts.

Harriet Jacobs, another notable abolitionist, documented a similar celebration in North Carolina, describing how children eagerly awaited the Johnkannaus. On Christmas Day, nearly 100 enslaved men paraded in vibrant costumes, collecting donations to fund their festivities, creating an atmosphere filled with music and dance.

However, the holiday season was not devoid of anxiety. Many enslaved individuals faced the looming threat of being sold or separated from their loved ones as the new year approached. This uncertainty often fueled a desire for escape during a time when slave owners were frequently distracted or inebriated.

John Andrew Jackson, owned by a Quaker family in South Carolina, exemplified this struggle. After being separated from his family, he successfully fled during the Christmas holiday of 1846, ultimately reaching Canada but never reuniting with his loved ones.

Similarly, Harriet Tubman capitalized on the holiday respite to rescue her brothers on Christmas Day in 1854, five years after her own escape.

During this time, many enslaved individuals also plotted revolts. In 1811, an uprising in Cuba, known as the Aponte Rebellion, was planned between Christmas and the Day of Kings. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution, enslaved and free people of color sought to challenge the institution of slavery.

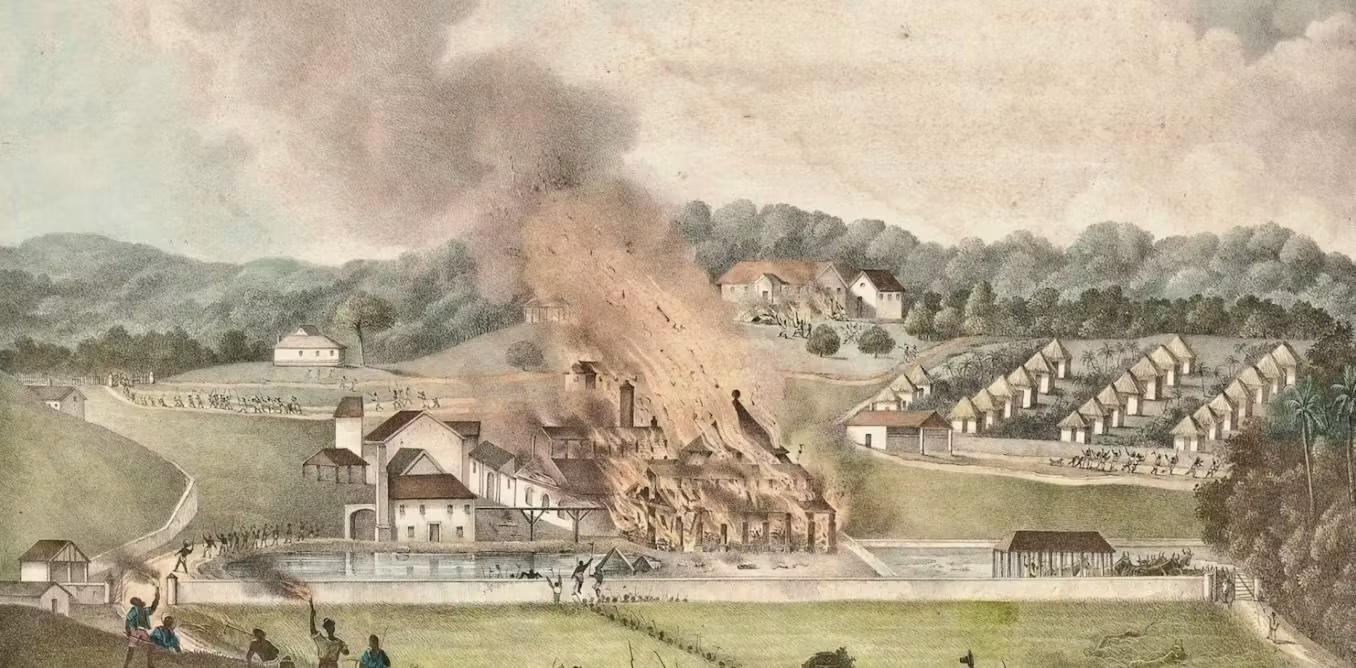

In Jamaica, the Christmas Rebellion of 1831, led by Samuel Sharpe, escalated from a strike for better working conditions into a large-scale insurrection. For nearly two months, enslaved individuals resisted British forces until the rebellion was ultimately quelled, resulting in Sharpe’s execution and igniting a wave of abolitionist sentiment in Britain.

Thus, the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day was significant for both feasting and plotting rebellion. It stood as a rare opportunity for enslaved men, women, and children to reclaim their humanity during a time of enforced hardship.