family

Black Communities Harness Mapping to Reclaim Their Sense of Place

Historian Carter Woodson established “Negro History Week” in 1926, which evolved into “Black History Month” in 1976. His vision extended beyond merely celebrating notable Black figures; he aimed to reshape how white America perceived and valued African Americans. Yet, significant facets of Black history often remain obscured by the emphasis on well-known individuals or pivotal events.

Recent studies highlight how African American communities have utilized maps to combat racism and affirm the value of Black life. The “Living Black Atlas” initiative emphasizes the overlooked tradition of Black mapmaking in the United States, showcasing innovative ways Black individuals have documented their narratives. Currently, communities are employing “restorative mapping” to share stories that reflect the reality of Black Americans.

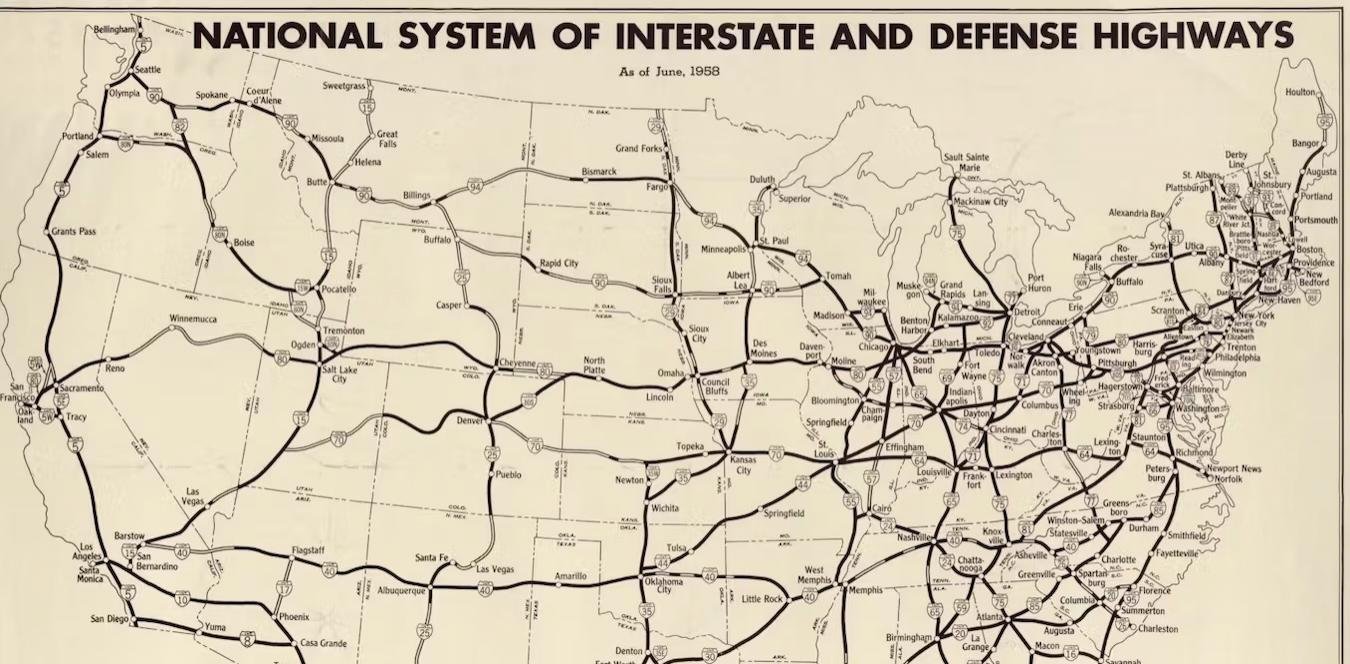

Maps are typically perceived as navigational tools, yet every map conveys a narrative. Historically, many maps have failed to accurately portray the experiences of Black communities. For instance, interstate highway maps often neglect the displacement of thousands of Black residents during the construction of these roadways. Marginalized groups, particularly Black individuals, have harnessed mapping as a means of countering oppression, offering dignity to their experiences through visual storytelling.

A key illustration of this practice can be traced back to the NAACP, which harnessed mapping in the early 20th century to advocate for federal anti-lynching legislation. By charting the locations and frequency of lynchings, they unveiled the pervasive nature of racial terror to the wider public. Similarly, during the 1960s, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) utilized mapping to document and protest systemic racism in the South. They created county-level maps highlighting income and education disparities, aiding activists in identifying urgent areas for civil rights demonstrations.

In a more contemporary context, artist-activist Tonika Lewis Johnson’s “Folded Map Project” juxtaposes addresses from racially divided neighborhoods in Chicago. By photographing the “map twins” and interviewing residents from corresponding locations, she illuminated the stark disparities that racism has produced in the city. This project facilitated conversations between residents from Chicago’s north and south sides, fostering understanding and connection.

Restorative mapping plays a pivotal role in the Living Black Atlas, providing visibility to marginalized Black experiences. One noteworthy project is the Chicago Black Social Culture Map (CBSCM), developed by Honey Pot Performance, a collective of Black feminists. This digital initiative chronicles the journeys of Black Chicagoans from the Great Migration to the rise of electronic dance music, interweaving historical records, music posters, and narratives about influential figures and venues.

The CBSCM seeks to engage Black Americans and tells Chicago’s story through artistic movements that reveal the profound ties African Americans have with the city. Amid ongoing gentrification and the displacement of Black communities, this digital map endeavors to preserve and honor these neighborhoods while sparking broader conversations about the history of Black Chicago.

At its core, restorative mapping aims to return something to its former state—a concept embedded in the restorative justice movement, which seeks to address historical wrongs by chronicling ignored injustices. The CBSCM is not a conventional map; it combines traditional geographical elements with links to literary works and cultural expressions, offering a rich narrative of Black life in Chicago. This initiative reveals how the geography of Black experiences continues to resonate today, encapsulating the essence of Black History Month.