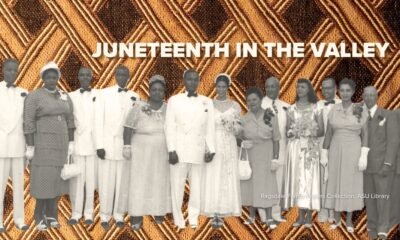

family

Juneteenth: A Glimpse into America’s 20 Days of Freedom Celebrations

On June 19, 1865, the Black dockworkers of Galveston, Texas, received the momentous news that freedom had arrived. This date, now celebrated as Juneteenth, marked a significant turning point, despite the harsh realities of continued oppression for around 250,000 enslaved individuals in Texas. The celebrations, mainly held in Black churches, often included speeches and shared meals, extending for seven consecutive days.

The jubilant response was ignited by Gen. Gordon Granger’s General Order No. 3, which proclaimed the emancipation of all enslaved individuals in Texas. However, this emancipation was part of a broader historical narrative. It was just one of many emancipations that began in the late 18th century, with significant milestones like the Emancipation Proclamation enacted by President Abraham Lincoln two years prior, on January 1, 1863.

Research reveals that between the 1780s and 1930s, over 80 emancipations occurred globally, with 20 instances in the United States from 1780 to 1865. However, many scholars argue that the freedoms associated with these emancipations were misleading. The laws enacted often retained systemic barriers, preventing Black individuals from gaining full citizenship rights. Discriminatory practices continued unabated, restricting voting and residential choices for newly liberated people.

Further insights indicate that these emancipations primarily benefited slave owners, as the process often required compensating them for lost property. This design reinforced white supremacy within societal structures. The concept of gradualism, prevalent at the time, suggested a slow approach to ending the injustices against Black individuals. Laws were crafted under this framework and viewed Black individuals as remnants of property rather than victims of a crime.

The 1780 Pennsylvania Act, for instance, appeared progressive but enacted reparations while perpetuating servitude for many newly born Black children, binding them to a system where they served until the age of 28. This pattern echoed through subsequent emancipations in Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey, all of which retained elements of this systemic bondage.

Post-Civil War amendments to the Constitution, including the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth, contained loopholes that continued to oppress Black communities. The Thirteenth Amendment allowed for the enslavement of incarcerated individuals, while the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments failed to adequately protect Black voting rights, opening doors for Jim Crow laws.

Gen. Granger’s Order No. 3 illustrated this ongoing oppression, outlining a model of labor relations that left many free individuals at the mercy of economic exploitation. The order advised freed people to seek wages but restricted their movements, emphasizing a new form of labor without true freedom.

Juneteenth celebrations therefore signify much more than mere emancipation. They embody a quest for justice amidst continued marginalization. As communities gathered to celebrate their resilience, they also called for an end to economic and racial injustices. Over the years, Juneteenth has evolved into vibrant public celebrations characterized by barbecues and parades, symbolizing both a historical acknowledgment and a push for systemic change.

In his posthumously published novel “Juneteenth,” Ralph Ellison poses a profound question about love and compassion in historical narratives, emphasizing that such inquiries remain relevant today.