arizona

Inmate-Led Initiative Revives Endangered Languages Behind Bars: ‘I’ve Never Been So Excited’

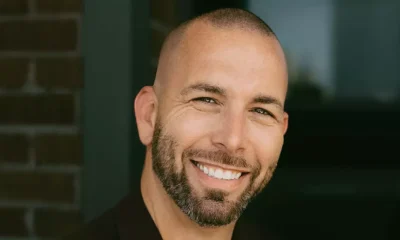

Thomas Steres, an inmate in the Arizona State Prison system for nearly a decade, has embarked on a remarkable journey of self-discovery and language learning. Before his incarceration, Steres served in the U.S. Navy as a Russian linguist. It wasn’t until about five years into his 15-year sentence that he began exploring his Welsh heritage through literature.

“It just spoke to me,” Steres remarked during a phone interview from Buckeye, Arizona. He has since taught himself to read, write, and speak Welsh, claiming a proficiency of around 60 percent. This self-driven pursuit aligns with a broader movement to strengthen the Welsh language, which, though stable, is still at risk, with only 17.8 percent of Wales’ population fluent.

Emphasizing the importance of language, Steres referenced a Welsh proverb: “A nation without a language is a nation without a heart.” His dedication goes beyond mere interest; he is actively contributing to the preservation of his heritage. Steres has partnered with Red Dragon America, a Welsh heritage organization, and has also written articles on Welsh culture for them.

Moreover, Steres has expanded his studies to include Brittonic, the linguistic ancestor of Welsh, and has collaborated on language-learning materials available on Spotify. His passion led him to establish the Linguistic Legacies Initiative at ASPC-Lewis, which now consists of nine inmates committed to studying endangered languages together.

The participants, incarcerated for various offenses, lack formal teachers and rely solely on books and resources from the outside. Steres dedicates about 10 hours daily to this endeavor, fostering an environment of collective learning. “We pretty much devote our entire days to this,” he explained, highlighting the structured routine they’ve developed.

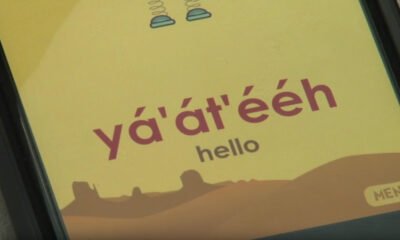

Joshua Huffman, another inmate in the program studying Taíno, expressed a desire to reconnect with his cultural roots. “It’s been beneficial to me. It changed my life. I’ve messed up most of my life, and now I’m doing something productive,” said Huffman, emphasizing the program’s transformative impact on his identity.

The initiative offers inmates a meaningful way to spend their time while in prison. Susan Dewey, a criminology professor, remarked, “People who pursue higher education in prison are those who want to change.” She noted that motivation in education significantly decreases the likelihood of recidivism. In learning new languages, participants also enhance their communication skills.

Although there has been no official response from state prison officials regarding this self-initiated effort, Steres hopes the program can serve as a model for rehabilitation. A GoFundMe campaign launched by the inmates’ families aims to raise funds for educational resources, and they aspire to eventually find a professional mentor for guidance.

The program also fosters unlikely connections among inmates. Steres noted the highly segmented racial dynamics within the prison system, saying, “This kind of breaks that down.” They unite across racial lines, learning not only about languages but about each other as well.

Omar Akram, another participant who studies Guosa, a language that integrates elements from various West African languages, shared similar sentiments. He observed a shift in himself and his peers since joining the program. “It just brings so many people, different ethnic groups and backgrounds together,” Akram reflected.

In a challenging environment rife with conflict, Akram found solace in the program: “I’ve never woken up and just felt alive in such a negative place.” He emphasized how the initiative provides a refuge amid the harsh realities of prison life, creating a space for growth and learning.